“I went to visit Paul’s grave today,” Lucy Kalanithi is saying in my ear.

It’s a sunny spring Thursday in northern California and the young widow of Dr. Paul Kalanithi (pronounced “Kuh-LON-uh-thi”) is spending her lunchtime chatting with me on a cell phone. I read her official bio as prep for this interview, and it summed her up this way:

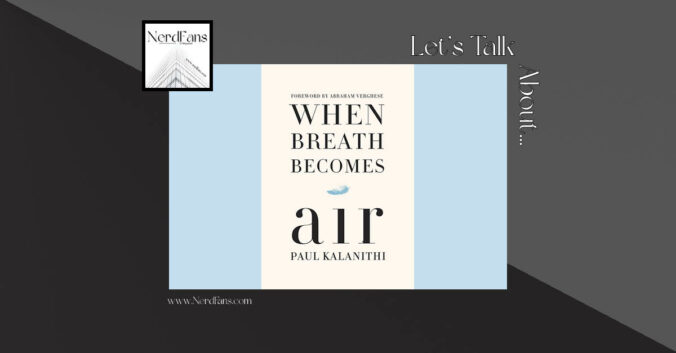

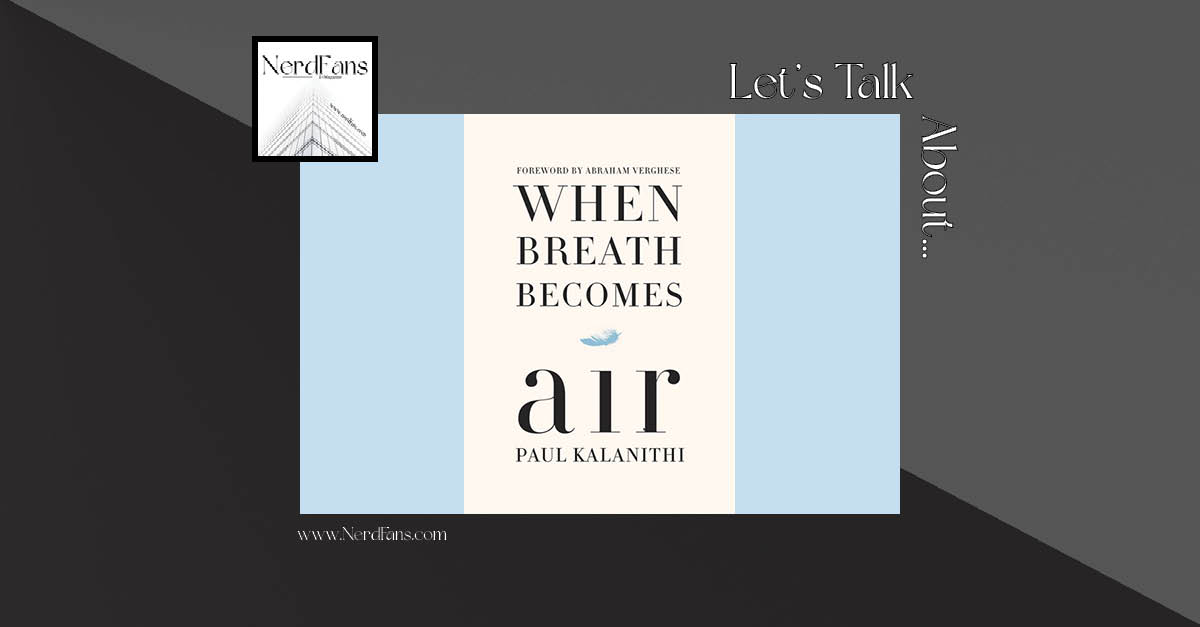

“Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, MD, FACP, is the widow of the late Dr. Paul Kalanithi, author of the #1 New York Times bestselling memoir, When Breath Becomes Air, for which she wrote the epilogue. An internal medicine physician and faculty member at the Stanford School of Medicine, she completed her medical degree at Yale.”

Suffice it say, I felt intimidated before she ever picked up the phone. But she’s been patient with my liberal arts education and we seem to be getting on just fine.

“I went to visit Paul’s grave today,” she’s just revealed, “with a friend this morning. But I was driving there by myself. It’s a winding road that takes you to the cemetery, which is near Half Moon Bay in California. I turned hymns on in the car. I have The Westminster Abbey Choir, and it gets me in a particular headspace. A contemplative, like reflective time. In a way it sort of stirs emotions that maybe I haven’t been attentive to when going through my to-do list and taking care of our daughter…”

I find that I don’t want to interrupt Lucy Kalanithi when she’s speaking.

We started our interview in a café but almost immediately she announced. “I might just go for a walk while we’re talking.” Then she was outside, in the streets, walking and talking and remembering. So for the last thirty minutes the melody of our conversation has been harmonized by things like a motorbike in desperate need of a muffler, random ramblings from passerby’s sidewalk discussions, traffic noises in the background and…laughter?

Wait, is that right?

Yes. As it turns out, laughter is very much a part of the Lucy Kalanithi experience.

Looking at her picture, reading her bio, remembering that she’s a widow and a single mother raising a small child, I expect her to be the somber sort. Intellectual. Gray-voiced and serious. Grown. Up. I guess she can be all those things when necessary, but her natural temperament appears to be something brighter, unreserved, more akin to joy.

Dr. Kalanithi laughs easily, and often. She gets excited about everyday moments. She’s warm and open and inquisitive and vulnerable. She says the word “like” a lot. And “sort of.” As in, “it’s sort of like…” She’s fascinated by living, yet an expert on death. And, well, she just seems at peace. Happy. I can’t help thinking this is the kind of doctor I’d like to greet me next time I’m sitting in a cold medical exam room waiting for a check-up. There’s life in her voice, and it feels contagious.

“I feel like having faith,” she’s saying to me now that the warbling motorbike has passed, “or even those hymns and traditions and songs as a touch point has been very grounding. It also feels as if it—I don’t know the right word!—elevates, or provides a meaningful context, and a communal context, for coping.”

Ah yes, coping would be required, I remind myself. He did die after all, didn’t he?

The Man Who Would Be Paul

For her first date with Paul Kalanithi, Lucy Goddard’s future husband took her to the circus-themed Barnum Museum in Bridgeport Connecticut.

For their last date, she followed him into a sterile hospital room and sat by his side while he died. It was Monday, March 9, 2015.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi was an accomplished neurosurgeon at Stanford University, in his mid-thirties, about to launch a long, productive career when he discovered he had metastatic lung cancer. He died two short years later, at age 37, leaving behind his wife and their infant daughter, Cady.

Sadly, many people die of cancer in America, so in that way Paul was not exceptional. What was unique about him though, extraordinary really, was that he chronicled his illness, beautifully telling his story from the perspective of both a patient and a doctor, exploring the breadth and depth and textures of a life preparing for death. Then, after their last date, Lucy completed her husband’s memoir, his final legacy, and shepherded it into publication. When Breath Becomes Air released January 2016 from Random House and became an instant bestseller.

Now, just over a year later, Paul’s widow and I are talking on the phone while she strolls peacefully though the glory of California’s trademarked sunshine. And she laughs. And occasionally tears up. And she remembers her husband for me, for us, sharing openly his beautiful sorrow, his tenacious hope, and the love that characterized his life…

§ § §

Lucy Kalanithi:

Paul used to say this thing where he would say, “We’re all guaranteed suffering. I hope we’re all guaranteed love.” Love and striving and suffering are kind of like the tent poles of what it means to be human, and also most of the world religions are built around that idea of love and suffering and striving. The biblical stories certainly provide that in Christianity.

There’s that part in the book where Paul writes about this, and this was a real conversation we had, obviously, when we were making the decision to have our daughter. We both were worried about each other. I asked him, “I worry that if we have a child, it’ll be so painful for you to die and know that you’re going die and you need to leave and say goodbye.” And then his answer was, “Well, wouldn’t it be great if it did make it harder?” We can’t avoid suffering. What we can do is attempt to find meaning.

Mike Nappa:

I’ve heard that one can suffer just about anything as long as there is purpose in the suffering.

Lucy

Oh! That’s so interesting! I think that’s been true for me, and certainly for Paul. Even if I think about my life over the past year since Paul died, taking care of our daughter has been a very clear purpose, and then making sure that Paul’s book came out was a really clear purpose. And then for my own professional path, I sort of felt disoriented for a while. Like I’m getting back on the academic track, but I’ve been on caregiver leave and maternity leave, and re-finding my footing as a widow and a mom. Like learning to be a mom and a widow at the same time as I’m returning to my career. And then finding a purpose in talking about end-of-life care and caregiving. You draw on what you’ve gone through, and you can’t predict it, you know?

Mike

By now we all know your husband’s story. What else would you like us to know about Paul?

Lucy

The thing that I think you can get a teeny sense of in the book, but not a full sense of, is he was really, really funny. I’m going to try and think of an example.

When he went to medical school he was worried that medical school would, like, beat the life out of him! Which didn’t end of happening. But sort of as a social anodyne around that time he slapped on a fake mustache, this big bushy mustache, on his face when he was getting his medical student ID photo taken. Like almost literally a Groucho Marx kind of thing! I think people would look at it and say, “Oh, was this guy a recent immigrant from India or something?” [Laughs] Like, what’s with this guy? It just sort of reminded him of who he had been before medical school, which was a writer and a sketch comedian, in college.

He was really, really alive, and he knew how to be reverent and irreverent at the same time. I don’t even know quite how to say it. But he was super funny, and he totally made me laugh, and he was really interested in what it means to be alive, whether that was reading serious literature or doing sketch comedy or doing brain surgery. He just was very interested in exploring the nooks and crannies of what it means to be human and be alive. Even when he was dying that’s what he was doing too. He was writing about death and life at the same time.

Mike

What part does your faith play when living through a situation like Paul’s cancer?

Lucy

We found it really helpful. I think some people, when they become ill or face a huge hardship, it changes their faith. They either become more or less faithful potentially. I think it’s interesting, Paul wanted to continue doing the same work as a neurosurgeon, and his faith remained really solid, but didn’t exceedingly grow or exceedingly shrink. What he had come to at that point in his life was really deeply considered, and so some things changed about him when he was sick, but his faith remained steady during that time.

Mike

You titled your husband’s book, When Breath Becomes Air. What does that title mean to you?

Lucy

He titled it! I think it’s really a striking title. It came from that little poem that’s the epigraph. That poem says, “You that seek what life is in death, now find it air that once was breath.” It’s a beautiful metaphor.

I remember sitting in bed with Paul—he was pretty ill so he did a lot of his writing either in bed or in a reclining armchair. He said, “Hey, I think I found the title for my book.” He’d been reading poetry, and he said, “I think I want to call it When Breath Becomes Air.”

It does kind of knock the wind out of you because it’s such a stark idea. It describes the moment of dying, when what was life and breath is now inanimate. It’s just air. That transformative process is so natural and so intense at the same time. And we had the opposite thing happening in our house too, which was Cady arrives and air becomes breath! It was this real mixing of both ideas. But I think it’s beautiful, and I think it suits Paul really well. And again, he chose the title.

The force of that idea, but then the fact that it’s also described really poetically, captures the sensibility of his book, and may be even why people are responding to it, because it’s the human exploration of something that is almost impossible to grasp.

Mike

When people speak to God about you, what do you want them to say?

Lucy

Ooh, wow! I guess I’ll just reflect on something. I mean, the thing that I hope for is peace and acceptance, so I guess I’ll share that. Like, even when Paul first was diagnosed and people said, “We’re praying for a miracle,” I would sort of think, “Oh, well you can just pray for peace.” Even if we don’t get a miracle, we can always use peace. That’s probably actually what we’re really going to need. That’s the thing I know we’re going to need!

Mike

I found that when my wife was battling cancer, at her worst, when I was actually starting to plan her funeral—

Lucy

Mm. Wow.

Mike

Oh, she survived!

Lucy

Yeah, yeah! But that’s an intense space to be in. That tells me how intense it was.

Mike

Yeah. I found that was the most unusual moment for me because I felt this intense, deep sorrow, and yet at the same time I felt this deep peace. This supernatural peace, just from God.

Lucy

Wow.

Mike

It was the weirdest thing. I had to actually stop and think about it. How do I feel this enormous peace in the midst of this enormous sorrow?

Lucy

And why do you think so?

Mike

I feel that God sometimes surrounds us with his presence. I mean, I feel he always surrounds us with his presence, and sometimes we are more aware of it than others. I think I was just aware of his presence at that time.

Lucy

Wow, that’s amazing.

I think about it, and I had that feeling on the day that Paul was dying. And I hope he did too, and I sort of sensed he did. Where it’s like “Nothing’s OK. And everything’s OK.” All at that same time.

Mike

Exactly. All right, well, It’s time to let you go. Thank you so much for taking time to chat with me today.

Lucy

Oh yeah! I was really glad to talk with you.

§ § §

Post Script

We hang up our phones. Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, MD, FACP, goes back to her life, and I prepare to head back to mine. But unexpectedly, I decide not to rush it. Not yet. I let silence fill my office, even forgetting to turn off the recorder that sits next to me.

“Jesus,” I whisper into God’s ear, “please continue to give Lucy Kalanithi the peace and acceptance that she’s asked for.” In the quiet I feel His presence, and I smile.

It’s nice to know He’s always near, both to Lucy and to me.

–MN