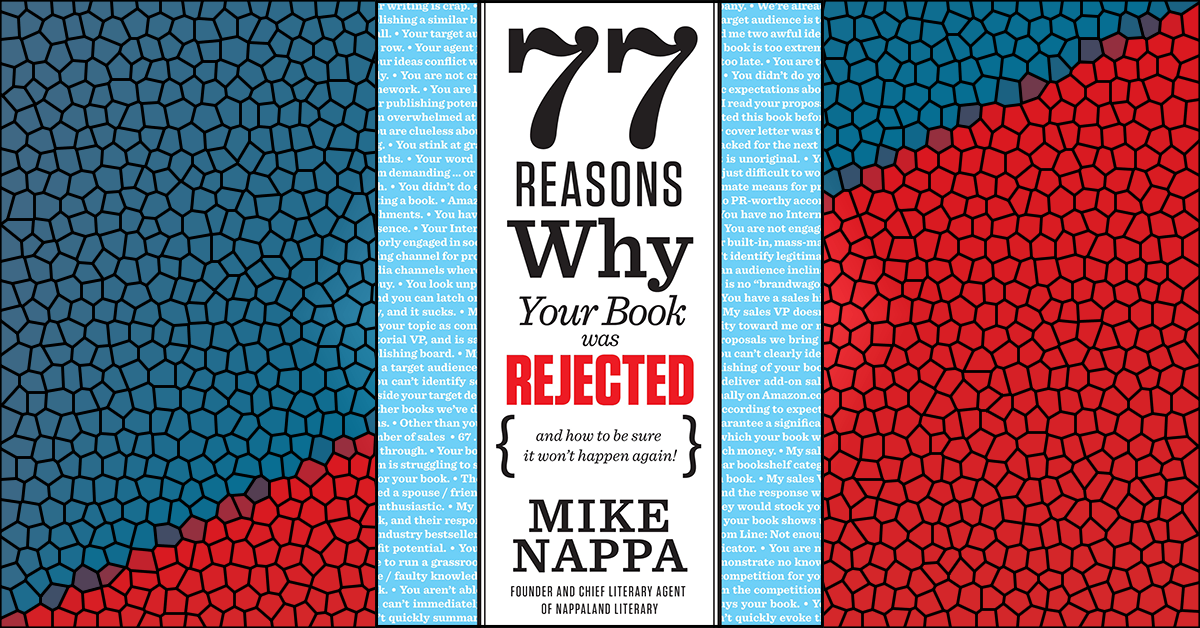

An Editorial Team reason for rejection

All right yes, it’s true: Crap writing gets published.

Crap writing often hits the New York Times bestseller lists. Crap writing sometimes even gets rave reviews.

But that won’t work for you. Here’s why:

Most often, crap writing is done by (or ghostwritten for) celebrities. You know, the pop singer who decides that because she can opine seductively about a sexual encounter in a three-and-a-half-minute radio single, she’s therefore qualified to write a children’s book masterpiece about small town America in the 1940s. Or the self-absorbed athlete who decides that because he’s a millionaire, people will buy his novel about a football team’s rise to glory. Or the young actress who pens her life story … at the tender age of 16. You get the idea.

But if you’re reading this book, my guess is you haven’t hit number 1 on the R&B charts, you never even had a tryout with the Dallas Cowboys, and Disney isn’t knocking on your door to star in a new series for preteens. I’m just sayin’.

What that means is, if you send me crap writing, I’m going to reject you. And I’m not even going to feel bad about it. I’ll feel like I’m doing humanity a service by keeping your stinky excrement off bookshelves everywhere.

And that’s the number 1 reason why an editor or agent rejects a book. Because

- your thinking is sloppy,

- the messaging is vain or irrelevant,

- the ideas are trite,

- the thought construction is ignorant,

- the content is poorly organized,

- the presentation is clunky,

- the word choices are abysmal, and….

Well, let’s just say it gives off an unappetizing odor when exposed to the world and leave it at that.

What You Can Do About It

1. First, Study the Craft of Writing.

Take time to learn what makes good writing good writing. How? Start by reading books you admire—first for the content, and then a second time to dissect the author’s techniques. Next pick up a few good books on writing from your local library or bookstore (see the appendix to this book for ideas). If you’re able, go back to college and take a few writing classes. Attend author signings and see if you can ask a question or two. Go ahead and take in a writer’s conference as well.

Whatever path your studies take, never assume that writing is something that just anyone can do. Do NOT say to yourself, “I’ve got a book in me!”(huge cliché anyway) and assume that means you are also competent to write a book. Don’t live on the false hope that the fantastic awesomeness of your idea somehow overrides your inexperience and ineptitude with the English language. It won’t.

Hey, you’d never assume you could pick up a cello and immediately play in the London Symphony, would you? So take the time to study the craft. It’ll pay off for you when your book proposal reaches my desk and smells like perfume instead of … well, you know.

2. Nitpick Every Word

Some think that writing means putting words on a page. That couldn’t be further from the truth. True writing means putting the right words on the page—on every page. So, before you send writing samples to me (or to any publishing professional), nitpick every word of every sentence in every paragraph of your work. Try to telescope from the macro (the big picture / plot / message / progression) to the micro (the individual sentences, words, and paragraph structure) and back again. Do this until every word justifies its inclusion in your masterpiece, and until everything from the start to the finish demands that the reader keep reading.

My suggestion? Write your manuscript a minimum of three times before anybody else sees it. First, write just to get the words on the paper (or into your computer file). Then rewrite to get the right words into the book—ruthlessly deleting the excess, harshly rewording lines that are unclear, trimming and slicing to make a concise, compelling whole, . Then rewrite yet again to make sure your “right words” aren’t really the wrong words in disguise. After you’ve put that much time and attention into writing your manuscript three times, you’ll likely be remarkably sick of the art you’ve created. Only then is it ready to show an editor.

3. Never, Don’t Ever, Nevernevernevernever Send Out Less Than Your Best.

Look, “good enough” is never good enough. So don’t hope that it is and then send it on its way. Instead, strive to shape every manuscript of yours into a work of art that’s painted with words. That’s the first step toward success in your writing career. And sure, it’s a big commitment. Are you willing to take that first step?

Looking for more? Check out these links: